The environmental, social and governance (ESG) conduct of a company has no direct bearing on its credit rating actions, which are focused on the short term, a research study by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) of more than 700 corporates has shown.

The study outcome reveals there have been no significant rating changes for all sectors globally since the ESG enhanced credit rating methodology.

If ESG considerations are deemed to have a credit risk or benefit but do not result in a tangible and timely credit rating change, what is the purpose of ESG considerations in credit ratings (or ESG credit score)?

“A company can have a weak ESG credit score, be carbon intensive or lack a clear carbon transition pathway, and yet be assigned a high investment-grade rating due to its high ability to repay its debt in the next three to five years,” says the report. Such companies may not suit investors who take the long-term view on investment, so even those that do not focus on ESG matters can be exposed to abrupt rating downgrades stemming from climate change.

Credit rating agencies have the potential to play an important role in driving sustainable debt financing, particularly in view of the need to carry out 70% of clean energy investment over the next decade to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, according to an International Energy Agency estimate.

As it stands, the current ESG credit rating methodology is a disadvantage for companies that are pursuing a sustainable transition. Credit assessment needs to be improved, and entities that pursue sustainability initiatives should be incentivized by enhancing low-cost financing to accelerate the clean energy transition.

The three agencies examined in the report — S&P Global Ratings, Moody’s Investors and Fitch Ratings — are increasingly viewing risk through an ESG lens to assess an entity’s creditworthiness, as articulated in their development of ESG credit scores. However, that is not enough.

“While the three agencies all provide detailed ESG credit scores to bond investors, it is difficult to establish a straightforward link between their ESG scores and credit ratings. Such scores merely represent a detailed and transparent ESG diagnosis on how these factors could impact the final credit outcome,” says Hazel Ilango, an Energy Finance Analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

As things stand, bond investors cannot adequately assess an issuer’s long-term credit risk based on the credit rating alone. They also have to refer to the ESG credit scores to somehow gauge its ESG exposure.

For example, offshore wind power company Orsted of Denmark has only a “BBB” credit rating from S&P and Fitch. In comparison, state-owned enterprise China Huaneng Group Co is reliant on fossil fuel and vulnerable to high stranded asset risks, but maintains a “A” credit rating range across all three agencies. This underscores the research finding that credit ratings do not change if a business model moves toward a low-carbon transition economy, until the company’s creditworthiness is affected.

Consequently, bond investors will continue to fund carbon-intensive companies due to their high investment-grade ratings, and decarbonization challenges will persist. IEEFA considers that the current methodology does not encourage debt financing of sustainable initiatives, so bondholders may keep supporting businesses that have fundamentally poor green standards. If the credit framework remains “business as usual,” real-world problems such as climate change and social inequality will continue.

Rating challenges and trends

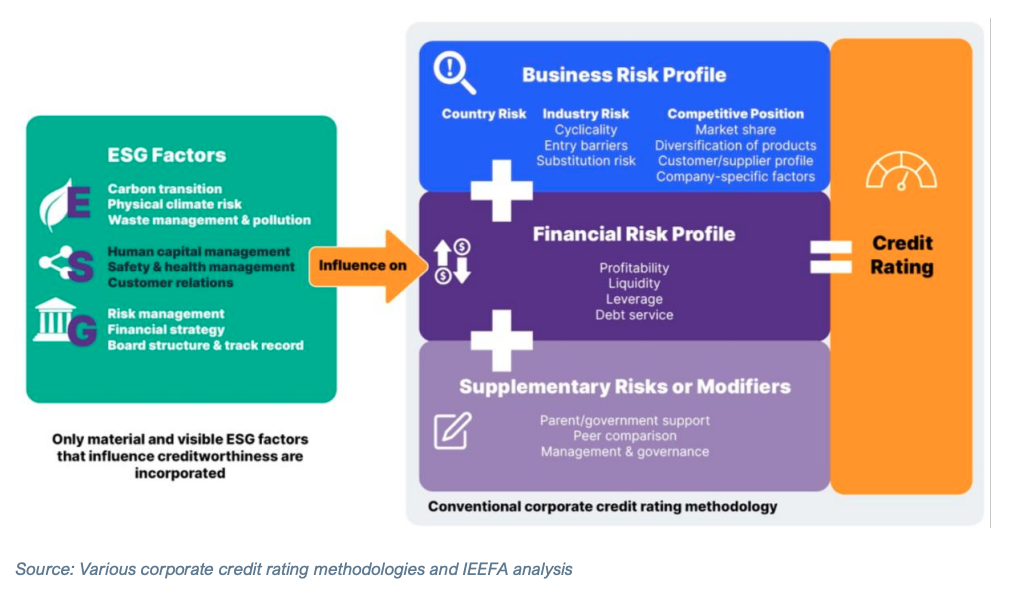

One of the challenges is a mismatch between ESG factors and the credit ratings time horizon. When evaluating ESG risks as part of a credit assessment, credit rating agencies consider four key factors: visibility, probability, severity and timing.

If ESG risks or factors are sufficiently certain, quantifiable and severe enough to affect creditworthiness, they are factored into rating considerations.

A carbon emissions tax, for example, would be a climate transition risk to include in financial forecasts, but the potential future cost of an extreme weather event would be excluded due to the uncertainty of its timing and impact.

Climate change risks expose bond investors not only to the physical climate, but also to transition risk with the shift toward a low-carbon economy. Therefore, corporates that are susceptible to such risks may have a higher potential for default.

Ilango cites the case of California’s Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E), which faced billions of U.S. dollars in liabilities related to wildfires, a physical risk, between 2015 and 2018. Subsequently, S&P and Moody’s downgraded PG&E’s rating due to its challenging environment, and the company finally filed for bankruptcy on 29 January 2019.

This highlights that what is deemed uncertain risk today could result in a multi-notch downgrade and, eventually, bankruptcy, which can severely impact bondholders. It also exemplifies how the current credit rating model is short-sighted and not intuitive enough to provide an early warning signal.

An issuer which faces heightened ESG risks in the long term, particularly climate-related risk, may experience an abrupt rating downgrade sooner than expected, raising the possibility of significant bond sell-offs.

Proposed Models for Integrating ESG Factors in Ratings

These challenges do not have a quick fix, given the complexity around credit evaluation. However, environmental and social issues are gaining traction and deserve more attention. The conventional rating methodology requires an overhaul to include long-term risk and produce a tangible outcome on credit ratings that account for ESG factors.

Just as businesses and risk managers are expected to think beyond the short term, so should credit rating agencies. However, this challenges the conventional perception of a credit assessment.

Ilango suggests carrying out standalone ESG risk assessment through qualitative scoring of environmental and social impacts on long-term creditworthiness, just as agencies are already doing in examining governance.

Rating agencies can also introduce double rating measures. For example, they can give a company a “BBB” rating based on the conventional credit assessment, then issue an upgrade or an ESG-adjusted rating to an “A” to recognize its substantial decarbonization strategy and robust social and governance attributes.

In addition, rating agencies could take a more granular approach to ESG considerations by including and publishing scenario analysis to quantify long-term trends and risk trajectories.